America 250

Countdown to America’s 250th Anniversary

On July 4, 2026, America will celebrate the most important milestone in our country’s history—250 years of American Independence. “With a single sheet of parchment and 56 signatures, America began the greatest political journey in human history,” said President Trump of this momentous anniversary.

Under the President’s leadership, the Salute to America 250 Task Force (“Task Force 250”) has commenced the planning of a full year of festivities to officially launch on Memorial Day, 2025 and continue through July 4th, 2026.

The White House is engaging and encouraging the entire federal government, state and local governments, the private sector, non-profit and educational institutions, and every citizen across this country to join in this historic celebration.

Task Force 250 invites citizens to have a renewed love of American history, experience the beauty of our country, and ignite a spirit of adventure and innovation that will raise our nation to new heights over the next 250 years.

As part of these efforts, Task Force 250 is proud to present an original video series, “The Story of America.” Read more below and check back soon for more details about additional White House initiatives.

The White House Salute to America 250 Task Force has partnered with Hillsdale College to provide a history series that tells the remarkable story of American Independence. It highlights the stories of the crucial characters and events that resulted in a small rag-tag army defeating the mightiest empire in the world and establishing the greatest republic ever to exist.

An Introduction

The Battles of Lexington and Concord

French & Indian War (1754-1763)

Despite its misleading name, this conflict (also known as the Seven Years’ War) was a war between the French and the British, from 1754 to 1763, throughout what is now the American Northeast, for control over the Ohio River Valley and eventual westward expansion.

Through almost a decade of fighting, the British ultimately prevailed, thanks to an impenetrable naval fleet and the strength of their American colonists and Iroquois allies.. The success of British forces was due in no small part to the fiscal liberality of William Pitt the Elder, who served as leader of the House of Commons in the middle of war, and later as prime minister. The generosity with which he amassed British resources was matched by his confidence, which he proved as British colonists faced losses abroad, and demand for his leadership grew at home: “I am sure I can save this country,” he said, “and nobody else can.”

After the war ended, the British gained control of Canada and all French lands east of the Mississippi River. They also found themselves overwhelmed by debt. To recover their losses, British Parliament taxed the American colonies from across the Atlantic, and the seeds of revolution were sown.

Stamp Act (1765)

In 1765, Britain faced a major financial crisis. After nearly a decade of war with France over control of North American territories, the empire had won vast territory east of the Mississippi River—but almost doubled their national debt. Keeping 10,000 troops in the colonies to maintain their hard-fought victory also added to the burden.

To raise money, the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act in March of 1765. The law taxed all printed materials in the colonies, including newspapers, legal documents, and playing cards. At the time, paper was expensive, and the new tax affected a large portion of the population.

Parliament believed the colonies should help pay for the troops that had defended them, but the colonists, accustomed to being taxed only by their elected assemblies, saw this as a violation of their rights because they had no representation in British Parliament. They responded with protests, boycotts, and riots.

The backlash was so strong that Parliament repealed the Stamp Act the following year, but the damage was done. The conflict revealed deep divisions and was an early sign of the growing unrest.

The Boston Massacre (March 5, 1770)

Tensions grew between Patriots and British soldiers in the years following the French and Indian War. In 1767, the British Parliament passed four acts known as the Townshend Acts, which included duties on lead, glass, paper, paint, and tea imported by the New World. Colonists in Boston, a major hub of commercial activity, urged boycotts of British products, and the Sons of Liberty, a group founded to protest the Stamp Act, identified shops that sold British products with the label “importer.”

In October 1768, the 14th and 29th regiments of the British army arrived on colonial shores, leading to escalating tensions. On February 22, 1770, a colonist who doubled as a British informer shot and killed 11-year-old Christopher Seider, who was in the crowd of protestors. Just a couple of weeks after the slaying, on the morning of March 5, rumors grew of the British planning to cut down the Liberty Tree, where effigies of men who favored the Stamp Act were hung.

On that cold night, a tussle that began with taunting ended with the eventual deaths of five patriots at the hands of British soldiers. Among those first patriots to be shot and killed by British soldiers was Crispus Attucks, a sailor of mixed African and Native American descent. Paul Revere’s depiction of the event fanned the flames of discontent among patriotic colonists, who increasingly found themselves bearing the yoke of servitude.

Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773)

On May 10, 1773, the British Parliament passed the Tea Act effectuating Prime Minister Lord North’s wish to salvage the struggling East India Company and increase revenue for King George III’s government.

Through the Act, British Parliament permitted the Company to sell their tea directly to American colonists and bypass American merchants, while still maintaining the taxes imposed on the colonies by the Townsend Acts less than a decade before.

Though the British claimed the Tea Act had the potential to lower the price of tea in the colonies, the Sons of Liberty encouraged their fellow colonists to resist the new show of British force that threatened colonial merchants.

Moved by the rallying cry “No Taxation Without Representation,” American colonists disguised as Mohawk Indians boarded British ships and dumped 342 chests of tea, worth over $1.7 million in today’s dollars, into Boston Harbor on December 16, 1773. As the Crown exerted more control over the colonies, revolutionaries began to rise up to resist tyrannical rule by a distant king.

Intolerable Acts (1774)

After Britain won the French and Indian War, it faced massive debt, both due to the war and due to multiple other factors, such as debts resulting from ongoing conflict with neighboring Spain. For this reason, British Parliament voted to tax their American colonies, telling colonial leadership that the taxes were necessary to ensure their own protection against Native American Indian attacks. Colonists did not view Native Americans as a continued threat and were outraged by this new form of taxation without representation.

After Britain won the French and Indian War, it faced massive debt, both due to the war and due to multiple other factors, such as debts resulting from ongoing conflict with neighboring Spain. For this reason, British Parliament voted to tax their American colonies, telling colonial leadership that the taxes were necessary to ensure their own protection against Native American Indian attacks. Colonists did not view Native Americans as a continued threat and were outraged by this new form of taxation without representation.

To punish the Massachusetts colonists, British Parliament passed four punitive laws in 1774. The Boston Port Act shut down Boston Harbor until the destroyed tea was repaid, crippling the local economy. The Massachusetts Government Act nullified the colony’s charter and limited town meetings. The Administration of Justice Act allowed British officials accused of crimes in the colonies to be returned home for trial in Britain, which the colonists viewed as a license for British officials to commit crimes without facing consequences. Lastly, the Quartering Act expanded the government’s power to house soldiers in private homes—a clear violation of property rights granted to all other British citizens.

These harsh laws, known as the Intolerable Acts, outraged colonists, united them against British rule, and sparked the convening of the First Continental Congress.

First Continental Congress (1774)

On September 5, 1774, the First Continental Congress convened at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to voice their opposition to British tyranny and establish principles common to all the colonies, including life, liberty, and property. Here, delegates from 12 of the 13 North American colonies met to reconcile their competing interests and to coordinate their resistance to British oppression.

On October 20, the Congress adopted the Articles of Association, committing the colonies to a total boycott of British goods if they did not repeal the Intolerable Acts by December 1, 1774, as well as an embargo on exports if they did not repeal them before September 10, 1775. In a further defense of their rights, the delegates approved the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress on October 14, 1774, which outlined the colonies’ objections to oppression and asserted their rights as British subjects. This document also discussed sending a formal petition directly to King George III.

Having taken measures to promote peace, the Congress took steps to prepare for war in case the British monarchy refused to accept their demands. Prominent Founding Fathers like George Washington, Samuel Adams, and Patrick Henry, used the forum to exchange ideas and information that laid the groundwork for armed resistance.

By galvanizing public opinion in the colonies, and generating widespread support for resistance, the First Continental Congress played a crucial role in advancing intercolonial cooperation. After disbanding on October 26, 1774, the Congress agreed to reconvene on May 10, 1775, for the Second Continental Congress.

Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty, or give me death” Speech

(March 23, 1775)

Following the increasingly tyrannical actions of the British government, including the Boston Massacre and British Parliament’s imposition of the Coercive Acts, which colonists called “The Intolerable Acts”, the Second Virginia Convention assembled in 1775 to deliberate the future of the American colonies and discuss the prospect of war.

Meeting at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Patrick Henry, a respected lawyer who served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, arrived at the Convention with the goal to galvanize militiamen into securing “our inestimable rights and liberties, from those further violations with which they are threatened.” Some members were wary of such decisive action, instead insisting that a peaceful resolution was possible. Growing impatient, Henry rose and delivered a powerful call to action to his fellow Virginians: “If we wish to be free…we must fight!”

At a moment when courageous action was needed, Henry’s address was delivered before more than 100 delegates, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and many of the statesmen that would go on to sign the Declaration of Independence. By a narrow margin, the Convention passed the resolution to begin plans for defending the colony—the first critical step to independence.

Henry’s famous words spoken at the pulpit of St. John’s Church—“Give me liberty, or give me death!”—remain instilled in the hearts and minds of every American citizen.

Paul Revere’s Ride (April 18, 1775)

Paul Revere, a Boston silversmith and committed patriot, was a member of The Sons of Liberty, which among other things, gathered intelligence and tracked British military movements. Working with Dr. Joseph Warren, Revere passed vital information to Patriot groups to protect their supplies and leaders from British raids.

On the night of April 18, 1775, Dr. Warren learned that British troops planned to march to Concord, Massachusetts to disrupt the American colonists’ plans and destroy their supplies. Revere sprang into action to warn his fellow Patriots of the impending British action.

Revere created a simple signal system using lanterns in the steeple of Boston’s Old North Church to warn local Patriots: one lantern if the British came by land, two if by sea. That night, two lanterns were hung.

Revere’s famous ride covered more than twelve miles. Along the way, he alerted a network of riders and key Patriots, helping ensure the militia was ready the next day at Lexington and Concord. Though Revere was briefly captured by British troops towards the end of his famous ride, he was released after being questioned and fortunately, he had already accomplished his mission to warn colonists that “the British are coming” prior to being detained.

While several riders played roles that night, Paul Revere’s swift warning and legendary ride became a symbol of American resistance and helped spark the first battles of the Revolutionary War. His bravery was memorialized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride,” which became a rallying call for liberty and equality for all at the start of the Civil War.

Battles of Lexington and Concord (April 19, 1775)

After years of intensifying hostilities between the British monarchy and the colonists, the prospect of war became inevitable. With Paul Revere’s fearless warnings that the British were marching to Concord to seize American arms, the local Minutemen–the armed militias formed in small towns to defend colonists’ lives and properties–prepared to defend homes and ammunition stocks. On April 19, 1775, the British arrived at Lexington and encountered approximately 77 American Minutemen led by Captain John Parker. The first shot was red. To this day, no one knows by whom. It became known as the “shot heard ‘round the world.” The British fired a volley, mortally wounding eight American heroes, the rest of thousands of soldiers to lay down their lives to achieve independence from Britain.

Later that morning, after the first shots were fired in Lexington, British soldiers, also known as Redcoats, arrived at Concord to destroy American military supplies. At the sight of smoke, 400 daring colonists descended down Punkatasset Hill towards the North Bridge to confront the British troops, where the British opened fire, killing 49 Americans. American soldiers then relentlessly ambushed the Redcoats, forcing them to retreat 12 miles back to Boston. The battles of Lexington and Concord included some 1,700 British regulars and over 4,000 colonists and raged over 16 miles along the Bay Road from Boston to Concord. One British soldier later was said to have recalled that the Americans “fought like bears, and I would as soon storm hell as fight them again.”

Adoption of the Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776)

The Declaration of Independence, adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, is one of the most beautiful and important political documents in history. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration not only proclaimed American independence from Great Britain, it also enshrined Americans’ natural rights as the cornerstone of our republic. “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” Jefferson masterfully wrote, “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

As the British laid siege to the continent and landed large armed forces in Boston and New York, many colonists grew to believe the only sure path to freedom was through independence. The Declaration also increased foreign support for the colonies, particularly from the French, who were persuaded that the conflict was a clear break from Britain, not an internal civil war.

The Declaration’s preamble makes clear that the colonies were establishing their independence based upon the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” The document also enumerates 27 grievances against King George III, rebuking his imposition of taxes without representation, the quartering of British soldiers in private homes, and the deprivation of trial by jury, among others. The signers conclude by pledging to each other, “our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

Battle of Brooklyn (August 27, 1776)

The Battle of Brooklyn was the first major conflict to take place after the Second Continental Congress declared independence from Great Britain and, in terms of troop deployment, it was the largest battle to take place during the entire Revolutionary War.

On August 27, 1776, twenty thousand British soldiers fought 12,000 American colonists for control of the Port of New York, which the British secured, and ultimately maintained, throughout the war. After George Washington’s momentous victory in the siege of Boston earlier that year, his defeat at Brooklyn was a blow to his confidence and that of his regulars.

The British took New York City and Long Island from the Continental Army through a successfully executed sneak attack, forcing Washington and his men to escape in the dead of night on August 29, when a thick fog descended on the area surrounding the East River. Many counted this fortuitous weather event as an act of divine assistance, upon which the Continental Army relied for the remainder of the war.

Battle of Trenton (December 26, 1776)

On Christmas night, 1776, George Washington and his Continental Army crossed the icy Delaware River into Trenton, New Jersey. This was a daring maneuver that culminated in the Battle of Trenton and would be historically remembered as a turning point in the American Revolution. This crossing was a critical strategic decision that boosted American morale and led to a series of victories.

The next morning, on the dawn of St. Stephen’s Day, American troops attacked Hessian soldiers—German mercenaries hired by the British—and captured almost a thousand from their ranks. After the army’s demoralizing defeat at Brooklyn earlier that year, the overwhelming victory at Trenton, which was obtained in just about an hour, gave the American troops the confidence they needed to keep fighting. A couple of days before Christmas, Benjamin Rush, a fellow signatory of the Declaration of Independence, recalled visiting Washington: “While I was talking to him, I observed him to play with his pen and ink upon several small pieces of paper.

One of them by accident fell upon the floor near my feet. I was struck with the inscription upon it.” This inscription read “Victory or Death,” reflecting Washington’s determination and resolve during a critical period of the American Revolution. Death he evaded, victory he gained, and the momentum Washington inspired the troops he led to Princeton for another unexpected triumph.

Battle of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777)

Two conflicts in 1777 at Saratoga, New York, proved to be turning points in the war. The first, on September 19, 1777 at Freeman’s Farm, saw an exchange between equally matched battalions end in a technical victory for the British but its army suffered heavy losses.

The second, on October 7, 1777 at Bemis Heights, marked a day of victory for Washington’s men, leading to General John Burgoyne’s surrender of 6,000 British troops, ten days after the battle’s conclusion. Benedict Arnold, the man who would eventually go down in American history as a “turn-coat” (a traitor who switched sides to the British), played a decisive role in securing the American victory at Bemis Heights.

The battle was also won, in part, thanks to the colonists’ use of non-traditional guerilla tactics that were influenced by Native American techniques, which confused the British amid already foreign terrain. The success of General Horatio Gates at Saratoga encouraged the French to aid the United States at a critical point in the war, initiating a friendship between the two nations that continues to this day.

Lafayette Comes to Help the Americans (June 1777)

At the age of 19, the Marquis de Lafayette crossed the Atlantic and joined General Washington’s Continental Army. Inspired by the promise of liberty made by the new nation’s Founding Fathers, and despite a royal decree prohibiting French officers from serving in America, Lafayette purchased his own ship, La Victoire, and landed on the coast of Georgetown, South Carolina on June 13, 1777, despite objections from his family and King Louis XVI.

Three months later, Lafayette offered his service to the United States without pay, and Congress named him a major general. By the end of the year, Lafayette was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine in southeastern Pennsylvania near the Delaware border.

Washington, who recognized Lafayette’s courage and genius for strategy, entrusted him with a major role in the Battle of Yorktown. Years after his victory in the battle that won the War of Independence, Lafayette returned to America and visited every state in the nation he helped preserve.

Valley Forge (December 19, 1777 – June 19, 1778)

Washington and his troops braved a brutal winter in an encampment at southeastern Pennsylvania’s Valley Forge from December 19, 1777 to June 19, 1778.

Through a combination of disease, malnutrition, and dreadful cold, an estimated 1,700 to 2,000 soldiers died at the camp. The hearts of the men who suffered there were strengthened by their faith in God and their loyalty to General Washington.

In General Orders issued on March 1, 1778, Washington assured his men: “Your General unceasingly employs his thoughts on the means of relieving your distresses, supplying your wants and bringing you[r] labours to a speedy and prosperous issue.”

With more than three years left to go in a war for independence, Washington sustained troops confronted by the horrors of war with the promise of victory through perseverance.

Battles in the South (1780 -1781)

The Revolutionary War began in the northeastern colonies and traveled southward to the homes of Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. The British Southern Strategy was a plan to win the war by concentrating their efforts in the south, where they anticipated more support from Loyalists, slaves, and Indian allies.

The strategy initially seemed to work, with Archibald Campbell’s capture of Savannah, Georgia in December 1778, followed by another British victory at Henry Clinton’s siege of Charleston, South Carolina, in 1780. British troops continued their tour through the south and gradually moved northward, with Charles Cornwallis’s victory at the Battle of Camden in northern South Carolina in August of 1780. But the tide began to turn when William Campbell’s American troops pushed back the British at the Battle of Kings Mountain in what is now Cherokee County, South Carolina, in October 1780.

Another American victory followed with Daniel Morgan’s defeat of the British at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, only to be followed by a victory by Cornwallis’s men at the Battle of Guilford Court House in Greensboro, North Carolina in March 1781. Though Patriots and the British traded victories throughout a series of southern battles in the last three years of the war, the Patriots ultimately held their own and Britain’s Southern Strategy failed to secure the victory they had planned.

Siege of Yorktown (September 28, 1781 – October 19, 1781)

The final battle of the Revolutionary War–the surrender at Yorktown, Virginia–marked the end of the lengthy war between the British and the new United States. A peninsula near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, Yorktown was the final fortification for Charles Cornwallis’s band of British troops and Hessian mercenaries.

The American victory at Saratoga achieved by General Horatio Gates in October 1777 was a pivotal moment in the American Revolution because it further convinced the French to formally ally with the American colonists, providing critical military and financial support. The aid provided by the Marquis de Lafayette and the troops led by the Comte de Rochambeau proved necessary for the victory won by Washington’s Continental Army. The French Navy, led by the Comte de Grasse, overcame the British at the Battle of the Chesapeake mere weeks before the final siege was waged, allowing the French to control the bay, and preventing Cornwallis’s men from escaping by sea.

Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781, at 10:30 a.m. The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, after months of negotiations between the American and British delegates following the American victory at the Battle of Yorktown. According to the Treaty, “His Britannic Majesty acknowledge[d] the said United States…to be free sovereign and Independent States.”

Articles of Confederation (November 15, 1777)

After members of the Second Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the body began drafting the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, the first governing document of an independent nation.

The Articles were finalized by the Congress on November 15, 1777, introduced to the 13 colonial states for ratification, and came into force on March 1, 1781, less than eight months before Washington’s ultimate victory at Yorktown on October 19, 1781. In the Articles, the only body existing outside of state governments was the unicameral legislature without the power to tax; neither an executive nor judicial branch was established.

Each colonial state was granted one vote, regardless of the size of a given state’s population. This system was designed to ensure that smaller states had equal representation with larger states, which led to a balance of power but also created challenges for decision-making. The system organized under the Articles’ drafters would be short-lived, as it lacked enough centralized control and spending authority to unify the states. The Articles of Confederation were superseded by the US Constitution just over eight years after their ratification.

Ratifying the US Constitution (1787-1788)

The organization of states formed by the Articles of Confederation soon found a successor in the United States Constitution. The longest-held national constitution in force in the world, this document created a separation of powers into three separate branches of government: the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The lack of national coordination found in the Articles was lamented by Federalists, including Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, among others. The three wrote a collection of 85 essays between October 1787 and May 1788, originally called The Federalist, and known today as The Federalist Papers. The political theories expounded in these essays clashed with both the rationale behind the original Articles of Confederation and the ideas of Anti-Federalists, who opposed a robust central (“federal”) authority, such as Patrick Henry and George Mason.

The pro-federal government essays addressed concerns about the inefficiency of the existing federal government under the Articles of Confederation and argued for a new constitution that would establish this central authority. Alexander Hamilton, for example, wrote in Federalist 70, “energy in the executive is the leading character in the definition of good government.” The authors of the Federalist Papers explained how the new Constitution would address the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, such as the inability to provide for common defense or maintain public order, while also ensuring the preservation of individual liberties and state rights. While the idea of concentrating central authority wouldhave been denounced during the drafting of the Articles, Federalist proponents of the Constitution ultimately found victory in a law of the land that has sustained a people for most of their nation’s 250 years. To assuage the Anti-Federalists’ concerns of the dangers of too much centralized power in the federal government, the states also ratified the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution, which enumerated individuals’ rights and states’ authority over any matters not explicitly stated in the Constitution.

Declaration of Independence Signers

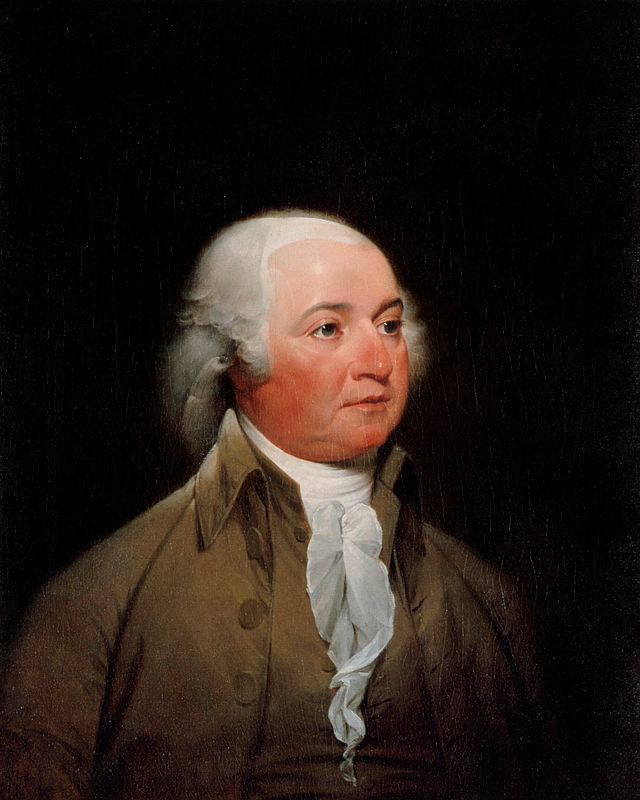

John Adams

America’s second President, John Adams was a lawyer, statesman, and political theorist whose writings and intellect were vital to American independence. In 1774, Adams was selected as one of Massachusetts’ delegates to the First Continental Congress. He returned the following year for the Second Continental Congress, where he helped draft the Declaration of Independence.

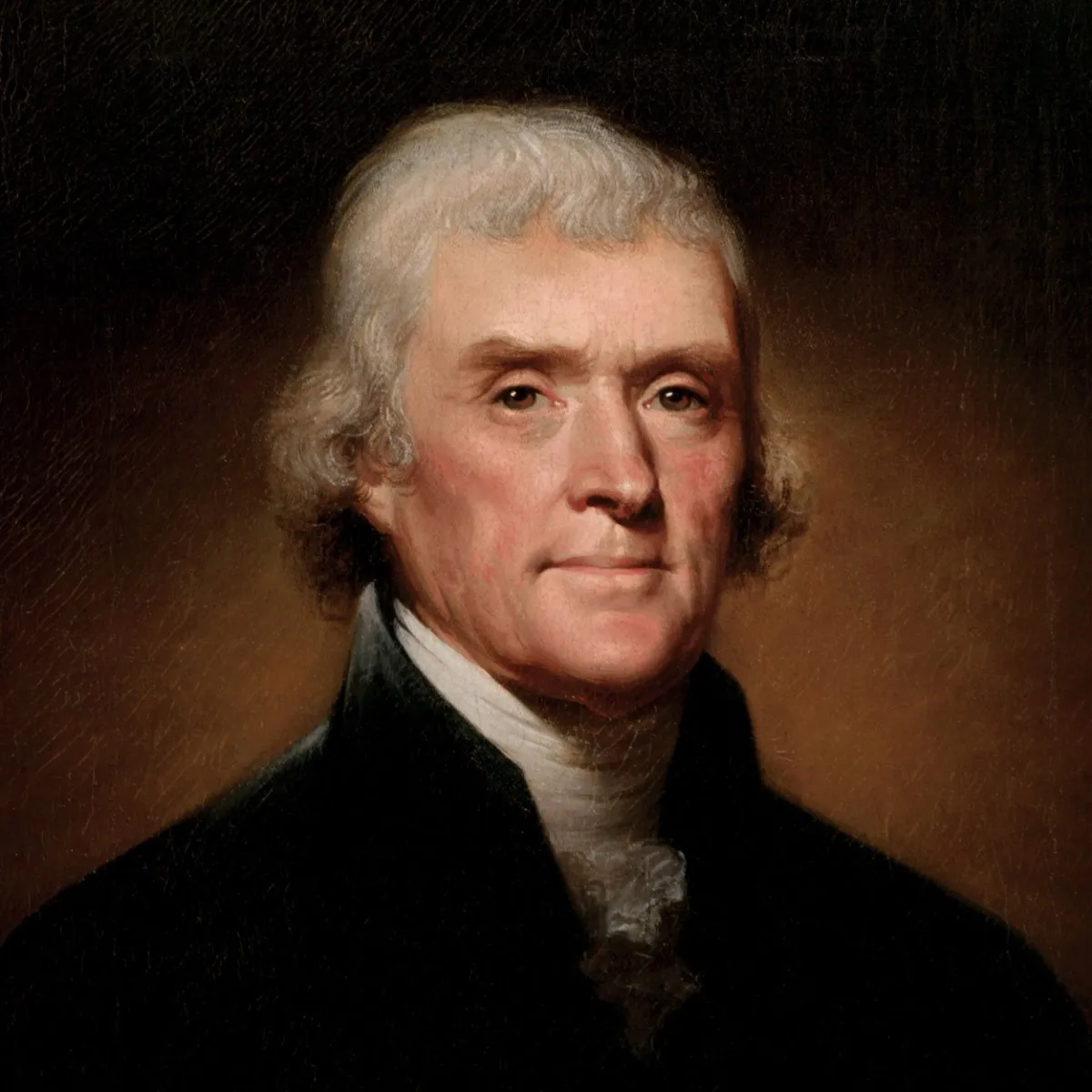

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the primary drafter of the Declaration of Independence and the third President of the United States. He penned the words that inspired thousands of young men to give their lives for the ideals that still ring true in the heart of every American: “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Benjamin Franklin

Born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin was a printer, writer, inventor, diplomat, and Founding Father. He was the most widely recognized American on the world stage at the birth of the United States. His wisdom and dedication to liberty helped shape the foundations of American democracy.

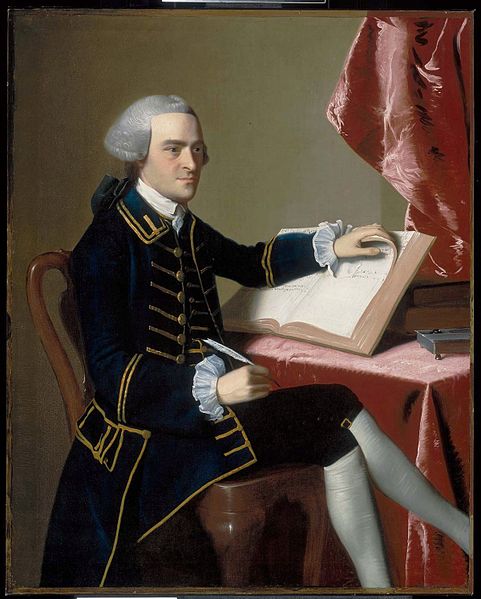

John Hancock

Born on January 23, 1737, in Braintree, Massachusetts, John Hancock is widely remembered for his prominent signature on the Declaration of Independence. His contributions to the founding of the United States extended far beyond that moment.

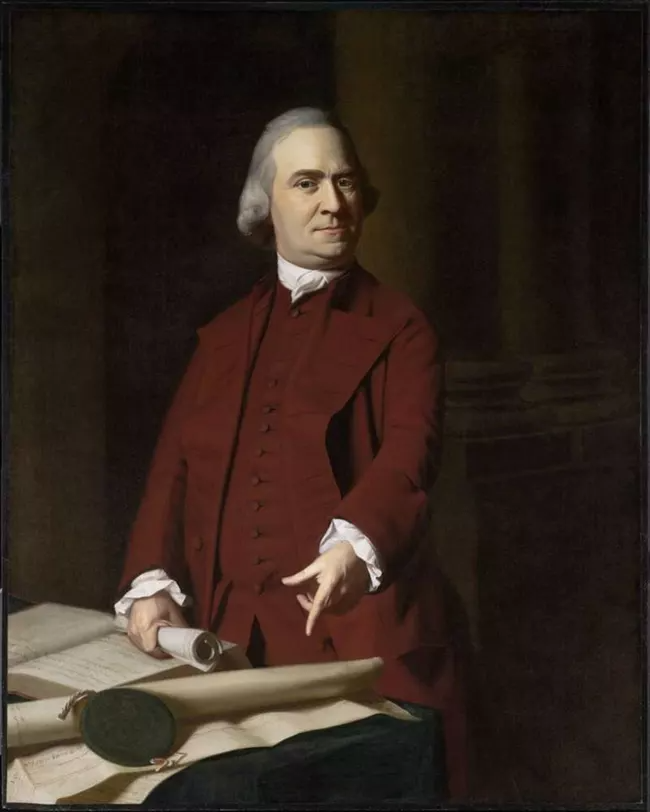

Samuel Adams

Born on September 27, 1722, in Boston, Massachusetts, Samuel Adams was a passionate and influential voice against British rule before and during the American Revolution. A second cousin of President John Adams, he played a major role in advancing the cause of independence.

Ladies of the Revolution

Martha Washington

Wife, mother, property owner, and the “First Lady” of the United States, Martha Washington was known for her personal strength, devotion to her husband, and patient resolve during and after the war.

Born Martha Dandridge on June 2, 1731, she learned to read and write at a time when many women did not. Throughout her life, she read the Bible, novels, magazines, and frequently wrote letters.

Abigail Adams

Advisor, writer, and trailblazer, Abigail Adams famously wrote to her husband John Adams to “remember the Ladies” as the Continental Congress gathered in 1776. She continued, “Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could.”

Phyllis Wheatley

Groundbreaking poet Phillis Wheatley is considered the first African American woman, and only the third American woman, to publish a book of poems. Wheatley was renowned for her imagination, drive, and courage.

Dolley Madison

Dolley Madison, the fourth First Lady and wife of President James Madison, was known for her influence, determination, and energetic presence. A frequent entertainer, she helped shape the role of the First Lady from the earliest days of the presidency.

Betsy Ross

Betsy Ross is credited with stitching the first United States flag—a symbol of freedom that has since become the marker of American identity, patriotism and pride.

Mercy Otis Warren

Known as the “Conscience of the Revolution,” and described as perhaps the most formidable female intellectual in eighteenth-century America, Mercy Otis Warren was a poet, historian, and playwright. She believed in the Revolution, and played an integral role in capturing, shaping, and moving the cause forward.

Create Your Own Founders Museum

Get direct updates

Stay in the know on America 250 and more.