The Debt Ceiling: An Explainer

By Chair Cecilia Rouse, Ernie Tedeschi, Martha Gimbel, and Bradley Clark

The United States hit its debt limit on August 1st, and the Treasury Department will soon run out of cash and other resources to stay below it, risking a default on obligations. Many do not fully understand what the debt limit is and the full impact of a breach. This piece explains the basics of the debt limit, the current situation, and the differences between a debt limit default and a government shutdown.

What is the national debt?

The national debt is the total amount of outstanding borrowings by the U.S. Federal government, accumulated over our history. The Federal government needs to borrow money to pay its bills when its ongoing operations cannot be funded by Federal revenues alone. When this happens, the U.S. Treasury Department creates and sells securities. These securities are the debt owed by the Federal government. There are many different types of Treasury debt; bills, notes, and bonds are the most common ones. The various types of debt differ primarily in when they mature—ranging from a few days to 30 years—and in how much interest they pay. The United States has not run an annual surplus since 2001, and has thus borrowed to fund government operations every year since then.

What is the debt limit?

The debt limit is a ceiling imposed by Congress on the amount of debt that the U.S. Federal government can have outstanding. This limit has been set at $28.4 trillion since August 1st, 2021.

It is also important to note that the debt limit is not a forward-looking budgeting tool that reveals what policymakers think are ideal levels of spending and revenue. Rather, it reflects the spending and revenue decisions debated and enacted in prior years by prior Congresses and Administrations; in fact, 97 percent of the current national debt stems from policy choices made before the Biden Administration took office in January 2021—choices made by both parties on their own and in a bipartisan fashion. The debt limit is the amount that the U.S. Treasury can borrow to pay the bills that have become due based on these prior policy decisions.

What happens when the U.S. government hits the debt limit?

Once the debt limit is hit, the Federal government cannot increase the amount of outstanding debt; therefore, it can only draw from any cash on hand and spend its incoming revenues. The U.S. Treasury can also take certain “extraordinary measures” to extend how long it can continue to pay all the government’s obligations while staying below the limit. These measures include accounting techniques within several government accounts that temporarily reduce the amount of U.S. Treasury securities issued to those accounts. These actions include suspending new investments or redeeming existing investments early. By reducing the amount of outstanding Treasury securities, the level of outstanding debt temporarily falls, slightly extending the amount of time that the government can continue to satisfy its obligations.

When the U.S. Treasury exhausts its cash and extraordinary measures, the Federal government loses any means to pay its bills and fund its operations beyond its incoming revenues, which only cover part of what is required (about 80 percent in 2019). While the United States has hit the debt limit before, it has never run out of resources and failed to meet its financial obligations. Take the debt limit crises in 2011 and 2013, for example; the debt ceiling was raised in the former episode (Congress raised the cap by an explicit dollar amount) and suspended in the latter (Congress eliminated the debt limit entirely for a specified period of time) in time, before the U.S. Treasury ran out of cash and exhausted all extraordinary measures. More recently, in 2019, the United States once again hit the debt limit, but Congress suspended the ceiling, eliminating the cap until August 1st, 2021.

When will the United States exhaust all of its resources?

The Federal government’s cash flows are hard to predict, which makes it extremely difficult to know the exact date when all extraordinary measures and cash will be exhausted. That said, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has stated that the government will likely run out of extraordinary measures if Congress does not raise or suspend the debt limit by October 18th.

Why can’t the Treasury Department just use the funds from incoming revenues?

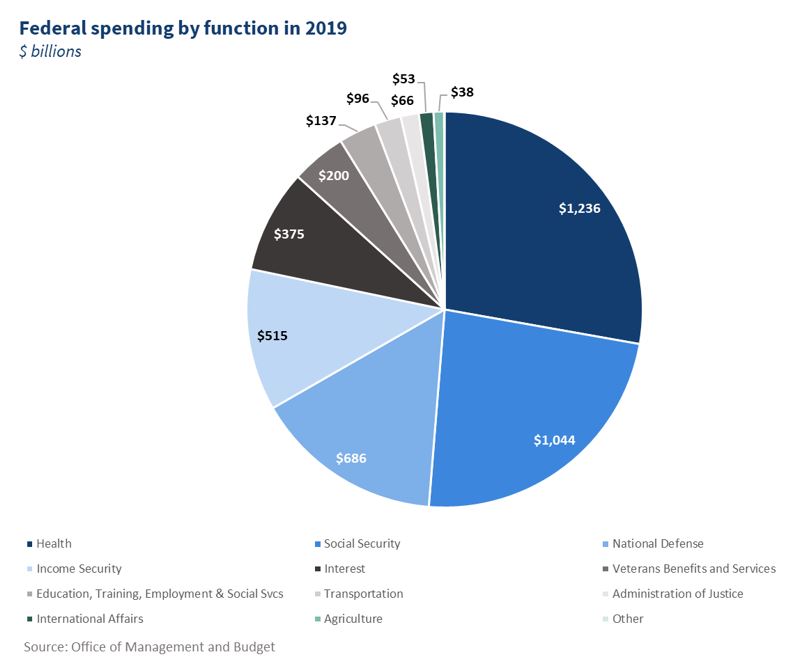

If the Treasury Department uses all of its extraordinary measures and cash, the government would have to pay all its obligations using only its incoming revenues. If these revenues happened to cover the promised payments, then the government would be able to meet its obligations. However, there are a few issues that complicate this hypothetical. First, the spending and revenue decisions were made in previous legislation enacted by Congress and Presidents of both parties. That previous legislation determines the relative sizes of revenues and spending today. For instance, if the Federal government has agreed to pay $10, but it only has $6 of revenue coming in, $4 of promised payments cannot be made unless additional debt can be issued to pay for it. Those promised payments could include programs like Social Security and national defense spending.

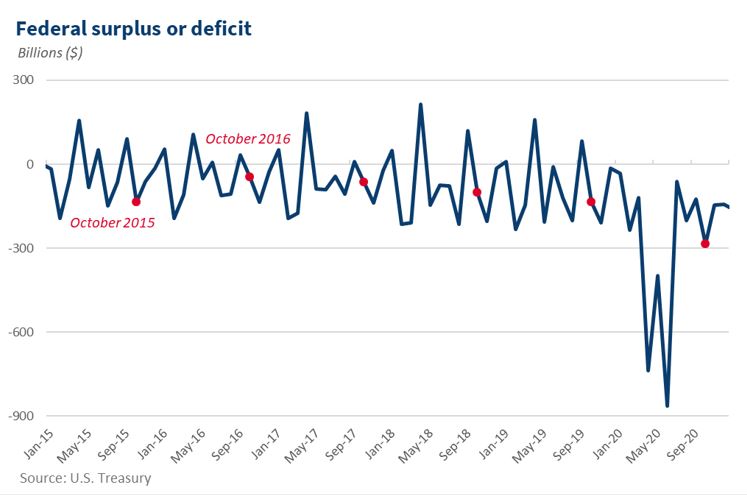

In addition, timing mismatches between spending and revenues mean that, more generally, the revenues would not cover the spending obligations. In certain weeks and months, it would be harder for the Federal government to meet its obligations than in others. Federal spending and revenues are both highly seasonal, meaning that they vary widely depending on the time of year, and they are often not aligned.

In October (when the United States is currently expected to exhaust its resources), revenues are generally lower than they are in other months, while Federal spending tends to be variable.

That means the Federal government will have relatively little money coming in to make payments on which people rely. For instance, in October 2019, gross Federal receipts were $261 billion and spending was $380 billion, meaning that if the government had exhausted its resources in October 2019, much of promised government spending would not have been paid.

What payments would be affected by exhausting available resources?

As noted above, if the Federal government exhausts available resources, the U.S. government would not have enough money coming in to make all of its payments. These payments go towards social programs that support households, such as Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance, and towards important government functions, such as our national defense and transportation. A breakdown of these payments can be seen below.

How is exhausting available resources different than shutting down the government?

Government shutdowns are entirely different issues from debt limit impasses. Government shutdowns occur when annual funding for ongoing Federal government operations expires, and Congress does not renew it in time. Since the Federal fiscal year begins on October 1st, shutdowns often occur around that time, but they can occur at other times if Congress authorizes shorter-term funding without renewing it in time later in the year.

Shutdowns still hurt the economy. For instance, research on the 2018–2019 government shutdown suggests that the quarterly level of real GDP dropped about 0.1 percent over the five-week shutdown. The 2013 government shutdown was estimated to reduce that quarter’s annualized GDP growth by 0.25 percentage point. Despite much of this loss in GDP being recouped in future quarters as delayed spending takes place, shutdowns still reduce overall economic activity, particularly through lack of consumption from government employees and delays in government services. However, the economic impact of a shutdown is a pale shadow beside the impact of defaulting on the Federal government’s obligations because of the debt limit.

What are the expected impacts if we were to default on our obligations because of the debt limit?

Because the United States has never defaulted on its obligations, the scope of the negative repercussions of not satisfying all Federal obligations due to the debt limit are unknown; it is expected to be widespread and catastrophic for the U.S. (and global) economy. Given that the U.S. Treasury is the global benchmark safe asset, a default would likely cause a financial crisis and recession. GDP would fall, unemployment would rise, and everyday households would be affected in a number of ways—from not receiving important social program payments like Social Security or housing assistance, to seeing increased interest rates on mortgages and credit card debt. For a more complete analysis of the expected effects of breaching the debt limit, see CEA’s accompanying blog post, “Life After Default.”