The Employment Situation in January

By Jared Bernstein and Heather Boushey

This morning’s jobs report reveals that the pace of job gains has slowed sharply in recent months as the pandemic continues to weigh on job creation, especially in face-to-face services. Strong relief is urgently and quickly needed to control the virus, get vaccine shots in arms, and finally launch a robust, equitable and racially inclusive recovery.

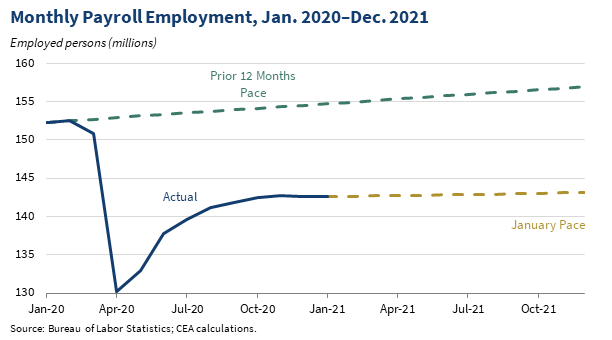

The economy added 49,000 jobs in January after losing 227,000 jobs in December. The three-month trend is weak. After downward revisions to the data for both November and December totaling around 160,000, the economy has added an average of only 29,000 per month. This pace is far below the rate necessary to pull us out of the pandemic jobs deficit—there are about 10 million fewer jobs now relative to February.

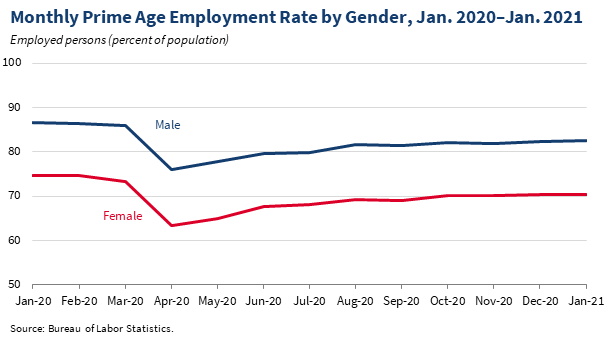

While job gains were weak, the unemployment rate fell to 6.3 percent, from 6.7 percent in December. This remains 2.8 percentage points above the rate in February 2020, before the pandemic. However, over this same time period, more than 4 million workers have dropped out of the labor force, disproportionately women.

Today’s employment situation release is yet another reminder that our economy remains in a hole worse than the depths of the Great Recession and needs additional relief to ensure that the pandemic can be brought under control, that families and businesses can stay solvent, and that workers can feed their families and keep a roof over their head. This month’s data gives us a sense of the scale of relief necessary and the economic costs of inaction.

This need for urgent, sustained action for the duration of this crisis is underscored by a few special questions that the Bureau of Labor Statistics added to its household survey. In January, just under 15 million people reported that they were “unable to work because their employer closed or lost business due to the pandemic.” This number has been about the same since October, after falling in the wake of the implementation of the CARES Act from May to September.

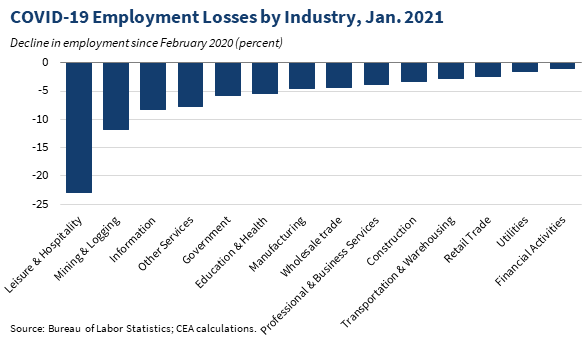

The small net job gains mask very different trends across industries. Some industries— including leisure and hospitality, education and health services, retail trade, transportation and warehousing, manufacturing, and construction—saw job losses, while others—particularly professional and business services, specifically temporary help—added new jobs. January’s data show an additional 43,000 jobs added in government, which likely partly reflected pandemic-related differences in seasonal patterns around school year hiring in state and local governments. The Federal government lost jobs.

Leisure and hospitality remains by far the worst hit industry, having lost 61,000 jobs in January on top of a downwardly revised 536,000 jobs in December, for a total of almost 4 million jobs lost since February 2020. This industry alone accounts for around 40 percent of jobs lost during the pandemic. Within leisure and hospitality, performing arts and spectator sports and accommodation and food services are suffering particularly badly. On the other hand, the financial activities sector, where workers can more easily telecommute, has held up relatively well, down only 1 percent from February 2020.

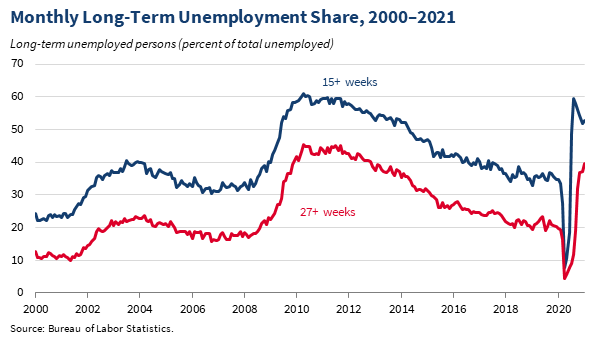

Long-term unemployment has risen, reflecting the duration of the economic crisis and the fact that the virus was uncontained during most of 2020. Almost 40 percent of workers in January were unemployed for 27 weeks or more, and over half were unemployed for 15 weeks or more. This partly reflects certain industries where finding work is difficult right now, in no small part due to pandemic precautions: the unemployment rate for leisure and hospitality workers is around 16 percent. The elevation in long-term unemployment is especially salient since benefits for these workers will expire soon without further Congressional action.

While the unemployment rate for men and women is relatively similar, women have left the labor force in staggering numbers. This phenomenon is reflected in the employment rate (or employment-population ratio) among women age 25 to 54, which is down 4.1 percentage points (2.6 million women) since February 2020, compared to a decrease of 3.9 percentage points (2.3 million men) among men. The larger decrease for women is unusual and likely reflects both the industries that this pandemic has hit and increased care responsibilities that have been pulling women out of the labor force.

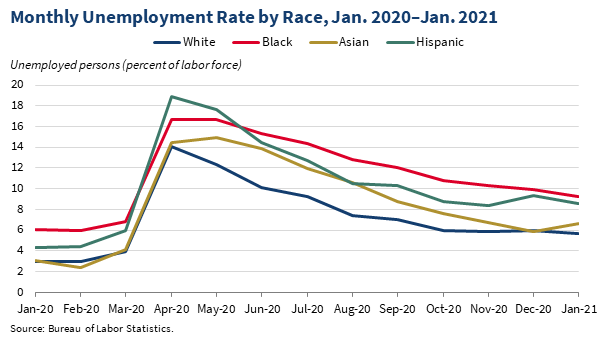

The headline unemployment number obscures wide variation across workers. Workers of color have been more likely to lose their jobs than White workers. In January, the unemployment rate for Black workers was 9.2 percent and was 8.6 percent for Hispanic workers, compared to 5.7 percent for White workers and 6.6 percent for Asian workers. The unemployment rate for Asian workers jumped suddenly in January to 6.6 percent, up around where it was in November after falling in December.

As the Administration stresses every month, the monthly employment and unemployment figures can be volatile, and payroll employment estimates can be subject to substantial revision. Therefore, it is important not to read too much into any one monthly report, and it is informative to consider each report in the context of other data as they become available.