Supporting Labor Supply in the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan

By Heather Boushey, Lisa Barrow, and Kevin Rinz

The economy can produce more goods and services by growing the number of people in the paid labor force, by increasing the number of hours worked by employees, or by increasing the output per hour worked, that is, increasing the productivity of labor. In the process, faster growth can help improve living standards. One way the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan aim to boost growth is by increasing U.S. labor supply through supports that meet the needs of workers’ families, making it easier for workers to participate fully in the paid labor market.

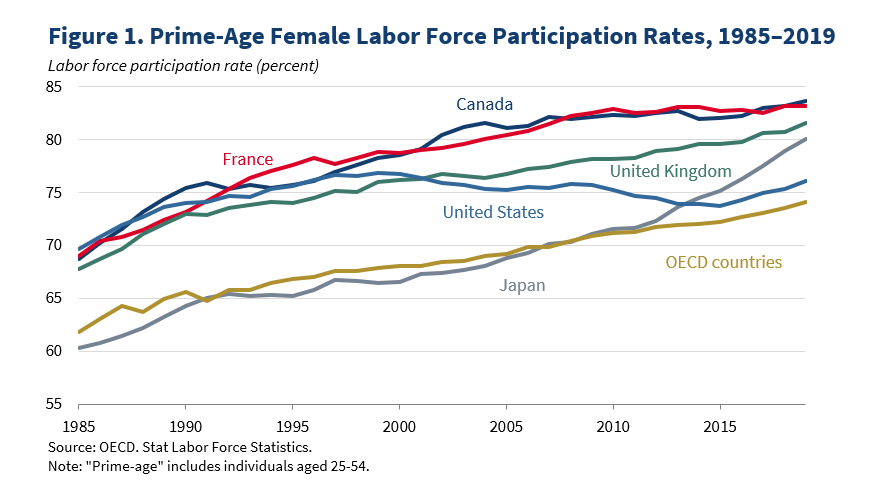

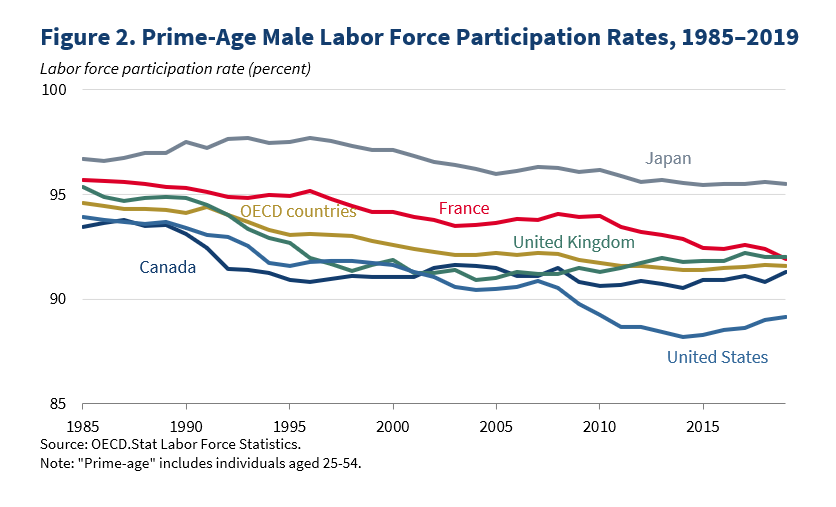

The United States has been falling behind its economic competitors in terms of the share of prime age men and women (ages 25 to 54) participating in the labor force (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). In 1985, U.S. men and women both had higher labor force participation rates than their Canadian counterparts. By 2019, U.S. men’s participation had fallen two percentage points below that of Canadian men, and U.S. women’s participation rate was more than seven percentage points below that of Canadian women. Stagnant or falling labor force participation represents a missed opportunity to increase U.S. GDP growth. For example, a one-percentage-point increase in the overall labor force participation rate could raise potential GDP growth by an estimated 1.0 percent.[1]

One important reason for the decline in labor force participation is that working families do not have the supports they need to both engage in employment and ensure quality care for children and other family members who need it, such as the aged or disabled. This is especially important for women workers. For example, one study estimates that lack of access to “family-friendly” policies, such as paid parental leave and childcare, explains nearly a third of the decline in U.S. women’s labor force participation relative to other OECD countries.

Within the administration’s proposed budget, three policies are specifically directed at increasing the quantity and quality of labor supplied by workers who also have care responsibilities: paid family and medical leave; expanded home health care; and expanded childcare and early childhood education programs. These provisions will provide income support to workers when they need time off to care for themselves or loved ones and ensure that when employees with care responsibilities are at work they have access to safe, affordable, and enriching options for their loved ones. Outside estimates are that, combined, the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan will increase the U.S. labor force participation rate by nearly one percentage point.

Paid family and medical leave. There are times when a worker needs to be at home rather than working outside the home, such as when a loved one is recovering from a serious illness or when a new child comes into the family, but 110 million workers lacked access to paid family leave in 2020, with low-wage workers being least likely to receive it through their employers.[2] The 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act provides about six-in-ten workers with unpaid, job-protected leave to care for a new child, care for a seriously ill family member, or recover from the worker’s own serious illness. While nine states and the District of Columbia have established paid family and medical leave programs that generally cover employees in large firms, for workers not in those places, those working in smaller firms, or those not employed by a company that voluntarily provides paid leave, the lack of guaranteed access means lost pay or an exit from employment. It is for this reason that the President’s budget includes $225 billion for a new, national program that would ultimately provide 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave to all workers, regardless of where they live or the size of their employer.

Research demonstrates that increasing access to paid family leave could make labor market outcomes more equitable. One study found that paid family leave increased hours worked and potentially earnings among mothers with one- to three-year-old children by around 10 percent; these effects are particularly strong among lower-wage mothers who were unlikely to be able to afford to take unpaid leave.[3] Evidence from California and New Jersey paid family leave policies indicates that even short-term duration paid leave around the time of giving birth can help increase labor force attachment of mothers in the United States, especially for women with less education who would otherwise not have access to paid leave. Furthermore, a 2011 study surveyed 253 California employers affected by the state’s paid family leave initiative and found that more than 90 percent of employers surveyed reported no negative effect on either their company’s profitability, turnover, or morale.

Home health care. Millions of workers have ailing loved ones in need of care, and with the aging of America, the need is likely to rise. According to the AARP, most of those who are caring for an ailing loved one—about six-in-ten—are also working for pay. In the absence of supports, family members are on their own to provide care, which often leads to reduced labor supply for caregivers. Home health care services can make all the difference in allowing a worker to ensure their loved one gets needed care so that they can stay in the labor market. The President’s budget proposes $400 billion in additional funds for home and community-based services under Medicaid.

Expanding funding for home and community-based services will not only allow more older Americans and people with disabilities to be served, but also improve the pay, job quality, and numbers of jobs for home-care workers. A recent paper has shown that the expansion of home care worker funding can support working families. By exploiting a change in Medicaid eligibility, the study demonstrates that expanding the availability of home health care services replaced unpaid time by family members, particularly adult daughters: “For every 2.4-3 women whose parent receives formal home care as a result of this policy, one additional daughter works fulltime.” Other research studying an expansion of home health care in Norway finds the expansion reduced the rate of extended work absences by family members most likely to serve as caregivers, such as adult daughters of elderly single adults. Higher pay for nursing aides has also been shown to improve health outcomes for those being cared for; thus, improving pay and working conditions for home health aides might also improve health outcomes, further reducing burdens on family members and supporting labor supply.

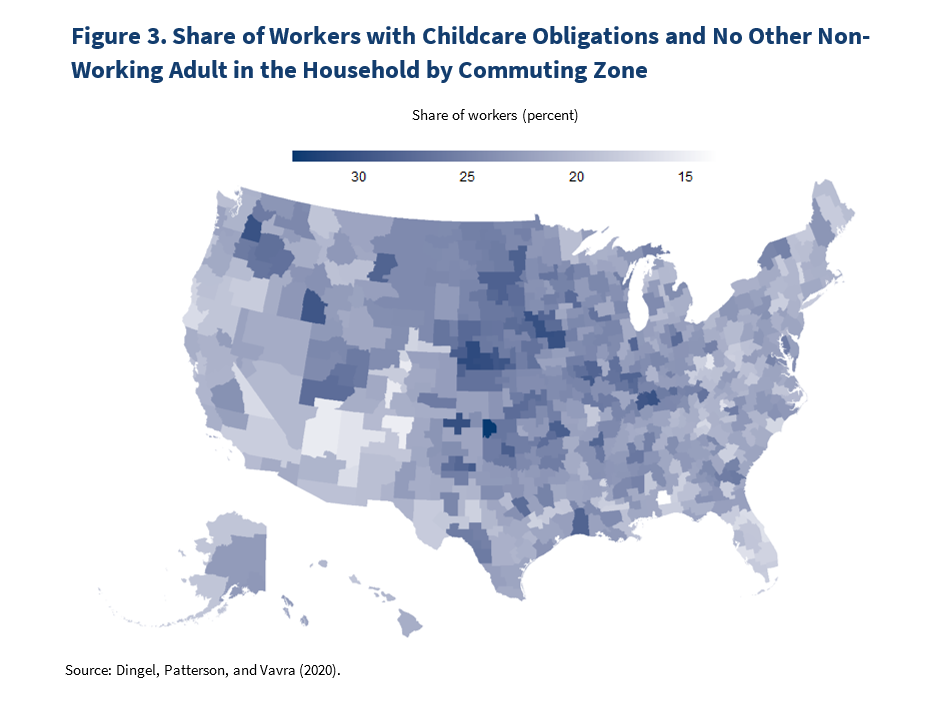

Childcare and early childhood education. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that childcare, preschool, and even elementary and secondary education are part of the nation’s care infrastructure. While the United States has free, universal access to primary and secondary school, it lags behind other developed countries in investments in childcare and early education. Lack of childcare can make it logistically difficult for parents to work outside the home. Indeed, many parents—particularly mothers—report that they work fewer hours than they would prefer or need to in order to care for their young children. For some parents there is no choice but to find outside care if they want or need to work: As found in a recent analysis, 21 percent of the U.S. workforce lives in households with no other non-working adult who could potentially serve as a caregiver (See Figure 3).

The President’s budget proposes $225 billion in new funding for childcare and $200 billion for universal preschool. The childcare plan includes an expansion of the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit and a commitment that low- and middle-income families will spend no more than 7 percent of their income on childcare for a young child. The universal preschool plan expands access to free, high-quality early-childhood education to millions of three- and four-year-old children.

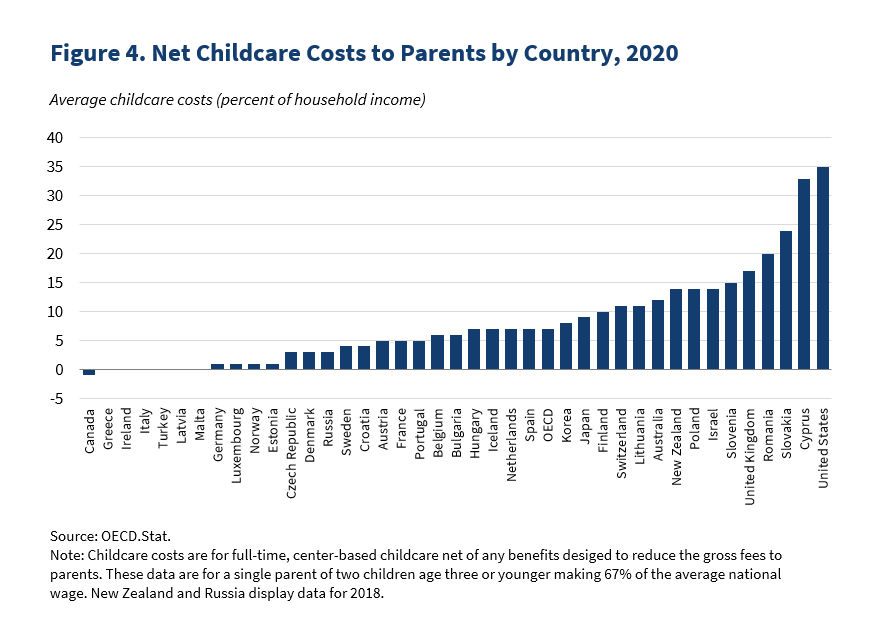

Research indicates that reducing the cost of childcare increases labor force participation among mothers of young children—thereby expanding the workforce, providing additional income to parents, and growing the economy. A recent review of research on childcare costs and women’s labor supply finds that a 10 percent decrease in the cost of childcare to families leads to a 0.5 to 2.5 percent increase in mother’s employment. According to OECD data, in the United States a single parent with two young children making two-thirds of the average wage spent about 35 percent of household income on childcare in 2020 (See Figure 4). The American Family Plan would limit such a family’s childcare costs to 7 percent of income. Estimates from the review mentioned above imply that this cost reduction could increase employment for these parents by between four and 20 percent.

A large economic literature also finds that access to childcare directly supports the employment of mothers, especially those with young children. The American Jobs Plan’s investment in building and upgrading childcare facilities will expand access to more areas of the country, and the American Family Plan’s universal preschool program will both reduce costs and expand access to care for parents of three- and four-year-old children. While preschool aims to meet the development needs of the child, there is also evidence from state experiments in universal preschool as well as from abroad that access to preschool affects maternal labor supply. Using both quasi-experimental analysis of funding expansions in the 1990s and data from a randomized control trial, researchers find that Head Start access increases employment among single mothers in the short-run. In addition, a study on the introduction of universal preschool programs in Georgia and Oklahoma finds that it may have increased maternal employment among mothers with a high school degree or less. Internationally, studies find that lowering the school starting age from age seven to age six in Norway increased maternal labor supply by five-percentage-points, and guaranteed access to preschool in Germany for three-year-old children led to a six-percentage-point increase in mothers’ labor supply.

The past year has highlighted how the care economy provides the foundation upon which families are able to engage in employment and be most productive. The President’s budget focuses on policies that will support long-term growth and stability. Ensuring that families have what they need to fully engage in employment is core to this agenda. It dovetails with other labor supply policies, such as expansions to Earned Income Tax Credit, or programs to get people into particular occupations, such as the Civilian Climate Corps, all designed to boost employment and increase productivity.

[1] This estimate uses growth accounting in a simple one-sector model and assumes a constant unemployment rate such that changes in labor force participation equal changes in employment. We further assume capital adjusts one-for-one to changes in employment as in a standard growth model.

[2] CEA calculation based on https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2020/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2020.pdf.

[3] The authors’ research is based on the effects of California’s paid family leave policy which was passed in 2002 and took effect in 2004. This was the first state paid family leave law.