Issue Brief: Supply Chain Resilience

Economic shocks caused by the Covid-19 pandemic severely disrupted global supply chains. At the same time, Covid-related shutdowns rapidly rotated consumer demand towards goods and away from in-person services. This collision of pandemic-induced supply shocks and strong demand for goods generated inflationary pressure across the global economy. As suppliers were unable to meet elevated demand, the true cost of highly-efficient, but fragile global supply chains became clear.

A growing economic literature shows that supply chains can be made more resilient. For instance, supply chains that rely on a broader diversity of input suppliers are more easily able to switch to alternate suppliers in the event of a concentrated shock to a large supplier (CEA 2022; MacDuffie, Fujimoto, and Heller 2021; Chopra and Sodhi 2014). As the pandemic faded, supply chains have improved. This issue brief documents this progress and describes ongoing efforts to prepare for future economic shocks by strengthening and diversifying supply chains.

Data presented below demonstrates that actions taken by the Biden-Harris Administration have helped to hasten supply chain normalization and put downward pressure on prices. After defining supply-chain resilience, this brief highlights existing areas where a lack of diversification could lead to increased fragility. The brief then describes current policy efforts to increase supply chain resilience, including through partnerships with allies that have already reduced bottlenecks and increased the diversity of inputs. Finally, it highlights the need to increase data availability for monitoring the health of supply chains.

Economics of Supply Chain Resiliency

A resilient supply chain is one that can easily adapt, rebound, or recover when faced with economic shocks that are either idiosyncratic—e.g., a local supplier plant shutdown—or systemic—e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic (Behzadi, O’Sullivan, and Olsen 2020; Ponomarov and Holcomb 2009). In the 2022 Economic Report of the President, resilience is defined as the ability of supply chains to recover quickly from unexpected events. Resilience can be achieved through better data on the structure of supply chains, investments in redundancy, greater ability to substitute between inputs, and improved communication across the supply chain (Council of Economic Advisers 2022).

Connectivity across global supply chains can threaten resilience because networks can, under some circumstances, propagate individual shocks across the broader economy. Economic research has long been clear that deeply intertwined supply chains can turn micro disruptions into macro-level effects (Acemoglu et al. 2012). Research has explored, for example, the fragility of supply chains and how disruptions at one firm can extend across the economy, and how diversified inputs and strategic sourcing can make supply chains more robust (Acemoglu and Tahbaz-Salehi 2020; Elliott, Golub, and Leduc 2022).

Inflation

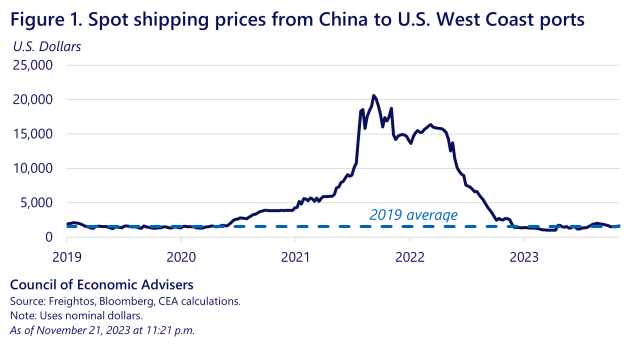

During the global pandemic, it became clear that global supply chains were propagating micro shocks into macro-level effects. For example, individual firms halted operations due to the spread of COVID-19, which created sectoral supply shocks that drove up prices. In the transportation and logistics industry specifically, a series of supply chain disruptions and delays at ports during the pandemic led to historically high prices for imports to the United States during the pandemic. At their highest point, spot shipping prices for containers coming from China to U.S. West Coast ports skyrocketed to more than 1000 percent of 2019 levels (see figure 1). The inflationary effect from the supply side was compounded by elevated demand pressures as consumers directed their spending towards goods, not services (Giovanni et al. 2022).

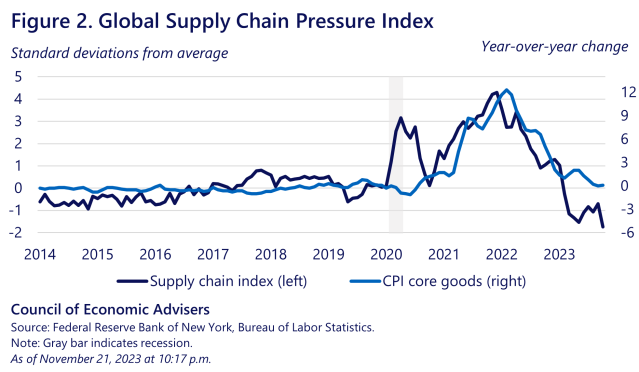

The correlation between supply chains and inflation can be seen in the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which tracks both headline and core goods inflation in the United States and the Euro Area (Giovanni et al. 2022; Council of Economic Advisers 2023). As shown in figure 2, the index grew sharply over the first year of the pandemic, reaching its highest-ever recorded value in April 2020, only to rise to an even higher peak by December 2021 (Federal Reserve Bank of New York). Since then, the index has come down significantly. In October 2023, it fell to 1.74 standard deviations below its historical average.

Recent research estimates that sectoral supply chain bottlenecks were responsible for a significant share of total observed U.S. inflation from 2021 to 2022 (Comin et al. 2023, Giovanni et al. 2022)). Santacreu and LaBelle (2022) also estimate that supply chain disruptions during the pandemic were a large component of cross-industry inflation for producers.

The resilience of supply chains is deeply connected to broader macroeconomic activity. For example, a recent working paper examined real sector activity across 64 countries and estimated that about 25 percent of the total real GDP decline during the pandemic was due to the effects of national lockdowns and their associated effects on labor availability which was transmitted through global supply chains (Bonadio et al. 2021). Disruptions from natural disasters also provide insight on the role of supply chains. A study of the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 found that the earthquake disrupted economic activity so much that in the year immediately after the disaster, Japan’s real GDP growth fell by 0.47 percentage point (Carvalho et al 2020). In addition, the earthquake had broader negative effects for indirectly linked firms up and down the supply chain. U.S. manufacturing output declined by one percentage point due to the sector’s supply chain linkages to Japan (Boehm, Flaaen, and Pandalai-Nayar 2019).

The Need for Diversification

Innovation in supply chain management has lowered the cost of production and generated economic efficiencies, at times at the expense of investment in resilience. Since the 1970s, many companies have begun adopting a “just-in-time” supply chain approach (Golhar and Lee Stamm 2007), where they produce goods to meet consumer demand with minimal excess capacity (Cheng and Podolsatky 1993; Mackelprang and Nair 2010). Just-in-time supply chain practices do not necessarily preclude inventory stocks that can make supply chains more resilient, but they often assume a relatively stable environment with minimal or few relatively small shocks (Choi et al. 2023). The original premise for just-in-time supply chains was that production and suppliers would locate in relative proximity, as opposed to the reality of global value chain networks that materialized across long distances (Kaneko and Nojiri 2008). Together, these factors make the just-in-time approach unable to absorb large shocks like those that occurred during the pandemic.

While shocks are inevitable—and weather-related shocks are likely to become more common over the next decade due to climate change—diversified supply chains are able to withstand shocks and recover when they occur (Baldwin and Freeman 2021; Martins de Sa et al. 2019). Greater diversity of input suppliers allows a firm to source from alternative providers if a shock disrupts the flow of input materials and components from one upstream firm. Boehm, Flaaen, and Pandalai-Nayer (2019) find that the primary reason why U.S. production suffered as a consequence of a Japanese earthquake was an inability of firms to substitute imported intermediates for domestic alternatives in the short run. One analysis estimates that diversification—adding more locations and suppliers for sourcing—can reduce GDP losses from large shocks by more than half for countries in the Western Hemisphere, including the United States (IMF 2022).[1]

The pharmaceutical and medical products industry is one particularly concerning sector where a lack of supply chain diversification has resulted in more frequent and prolonged shortages of critical consumer goods (e.g., cancer drugs). Kim and Scott Morton (2015) document trends in new and ongoing shortages of pharmaceutical products in the United States beginning in the mid-2000s. Examining the market for injectable drugs, Galdin (2023) concludes that offshoring has increased risk in pharmaceutical supply chains—where firms’ cost-cutting incentives overshadow the benefits from investing in resilience and extra capacity.

It is likely that both domestic and international diversification is required to increase the resilience of supply chains. Increasing supply chain diversification is distinct from boosting U.S. production capacity, although the two can work together to promote common goals. For example, Bonadio et al. (2021) finds that global diversification is critically important during a nationwide shock which may limit key domestic inputs.

Greater diversification—including through trade—can improve resilience against acute and long-run economic shocks. For example, after a plant closure resulted in an acute infant formula shortage in the United States during 2022, the Biden-Harris Administration worked in partnership with domestic suppliers to increase supply while simultaneously lowering administrative barriers to encourage imports (White House). Looking forward, the physical and transition risks of climate change, geo-economic tensions, and the rise of digital technology (e.g. due to cybersecurity threats) are all sources of systemic risk to supply chains in both the near- and long-term (Baldwin, Freeman, and Theodorakopoulos 2023). For instance, to address such risks, the White House, in partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is monitoring developments related to El Niño, including potential disruptions to global supply chains and their impact on trade, food security, and human health (White House).

Increasing Diversification

The public sector has an important role to play in improving supply chain resilience. Legislation can prioritize investments in supply chain resilience in targeted sectors that are critical to national and economic security and have large spillover effects, including semiconductors, energy production, transportation, and health. Supply chains cross international borders, and the public sector is uniquely capable of facilitating international cooperation to prevent or mitigate economic shocks and increase the ability to substitute inputs in the event of supply chain disruptions (Council of Economic Advisers 2022).

Addressing Supply Chain Concentration

Information on potential vulnerabilities is central to public and private sector efforts to improve supply chain resilience. A 2021 executive order directs a whole-of-government approach to address threats to the United States’ most critical supply chains (White House 2021). The first step of this process involved 100-day agency reviews into specific supply chain issues, which identified opportunities for investments across key supply chains where—absent policy—the United States could be vulnerable to future shocks. Subsequently, seven Federal agencies conducted deep-dive industrial base reviews of critical supply chains, building on the insights from the 100-day reviews.

The reviews revealed vulnerabilities in a number of key industrial sectors due to supply chain concentration. For example, for each of the key battery material inputs lithium, cobalt, and graphite, a single country controlled at least 60 percent of one or more stages of global production (Department of Energy 2022). In semiconductors, 88 percent of semiconductor production occurs overseas, reflecting a decline in U.S. manufacturing capacity over time (Department of Defense 2022). Similarly, the Department of Defense identified 37 critical minerals where more than half of global production relied on a single country (The White House 2021).

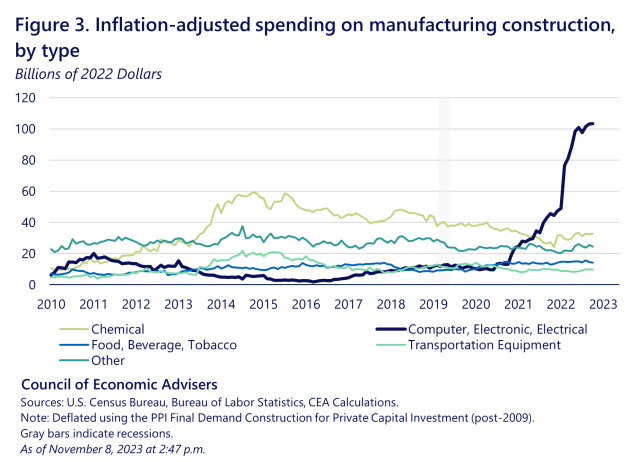

Based on the supply chain reviews, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS & Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act were passed and signed into law by President Biden to address key supply chain vulnerabilities. Together, these laws have leveraged public-private partnerships to spur private sector investment in domestic manufacturing and its raw material inputs. As of November 2023, private companies have announced more than $614 billion in planned investment in industries including semiconductors, electric vehicles, and batteries. These commitments are translating into tangible spending. For instance, compared to January 2021, inflation-adjusted spending on construction of manufacturing facilities had nearly doubled by September 2023.

This boom in the construction of new and expanded manufacturing facilities has been driven by certain critical industries where manufacturing capacity had become disproportionately reliant on concentrated foreign suppliers. While inflation-adjusted construction in other manufacturing industries, like those related to food and beverages, has remained roughly static, the sharp increase has been driven by a spike in investment across computer, electrical, and electronic industries. In September 2023, there was over $100 billion (at an annual rate) in investment for the construction of these manufacturing facilities. This includes plants for semiconductor fabrication and battery manufacturing—a more than 8.5-fold increase compared to the 2019 average (see figure 3).

Industry-Specific Actions

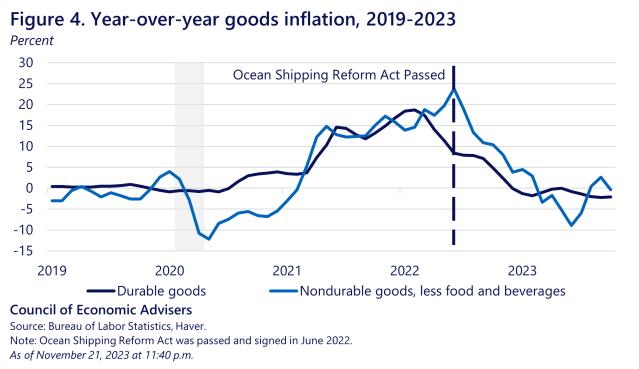

The Biden-Harris Administration worked in partnership with Congress to put in place new legislation to alleviate specific supply chain disruptions and promote greater resilience in the future. Prior analysis has shown that international shipping costs can translate into broader U.S. inflation (Sly et al. 2016). In June 2022, President Biden signed the Ocean Shipping Reform Act to address port and ocean shipping challenges. The legislation allows the Federal Maritime Commission to introduce a ban on unfair and discriminatory practices for shipments and authorized the Bureau of Transportation Statistics to collect additional data about dwell times at various ports, among other provisions. Following these legislative reforms and other Administration efforts to promote competition, ocean shipping prices have normalized to 2019 levels after their 10-fold increase during peak bottlenecks, coinciding with declining goods inflation in late 2022 (see figure 4).

International Partnerships and Collaboration on Resilience

The Biden-Harris administration is working in partnership with global partners and allies to build resilient supply chains across a globally integrated economy. In 2021, President Biden held a Summit on Global Supply Chain Resilience with partners from the European Union and 14 other countries to discuss opportunities for collaboration on embedding resilience into global supply chains.

The Biden-Harris administration is also working with allies to develop shared standards for manufacturing, investment, and production to ensure that international efforts are mutually reinforcing. For example, the United States has launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) in partnership with Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. One of the framework’s four pillars focuses on supply chains, including by establishing an IPEF Supply Chain Council and an IPEF Supply Chain Crisis Response Network. The crisis response network can serve as an emergency communications channel in the event of acute supply chain disruptions to help minimize impacts on workers, businesses, and consumers. Together, IPEF encourages deeper trade relationships with close economic allies and promotes high standards around data flows, privacy, labor, and the environment. The Administration also launched a new U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, which focuses on promoting U.S. and EU competitiveness in advanced technological products and advancing U.S. and EU collaboration. For example, the United States and the European Union created a joint early warning mechanism for semiconductor supply chain disruptions with a playbook to follow in the event of a future large disruption (White House 2023).

The United States has prioritized engagement with allies on critical supply chains, including those relevant to building the clean energy economy. In particular, critical minerals and materials will be essential for a variety of clean energy technologies, including batteries (for EVs and energy storage), solar modules, and others. The United States developed a Minerals Security Partnership with Australia, the United Kingdom, the European Union, South Korea, and others to mobilize private sector investments in projects to support mining, extraction, processing, and recycling of these critical minerals that enable the transition to zero-carbon energy. Also, the United States is engaging in bilateral negotiations with countries to develop critical minerals agreements, like one signed with Japan in 2023, to promote a more diverse supply chain by lowering trade barriers.

Improving Data Availability

To improve supply chain resilience, the public sector can collect and disseminate information that can help markets work more efficiently and allow firms to anticipate and prevent supply chain disruptions. In addition to the supply chain reviews conducted early in the administration, the Federal government is therefore making strategic investments to improve supply chain resilience by facilitating improved data availability and flow.

To assess, strengthen, and scale clean energy supply chains, the Department of Energy created a new Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains in 2022. The new office houses novel supply chain data and analytical capabilities, which will inform decision-making across the Department of Energy, including investment decisions that will support scaling up and deploying new technologies.

Meanwhile, for medical products and pharmaceuticals industries, in March 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services established a new Supply Chain Control Tower program to respond to public health needs created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The program leveraged information from across the U.S. government (including national stockpiles) and private industry players (such as distributors and manufacturers) to provide a real-time monitor of the supply and demand of critical goods like protective equipment necessary for the pandemic response.

The Federal government has also leveraged public and private data sharing to help ease supply chain disruptions in the transportation and logistics industries. Specifically, the Department of Transportation established the Freight Logistics Optimization Works (FLOW) initiative in March 2022, run by the Department’s new Office of Multimodal Freight and Infrastructure Policy. The initiative brings together public entities and private businesses operating in the logistics industry including port authorities, ocean carriers, terminal operators, warehousing companies, and goods-oriented businesses. FLOW functions as a digital information exchange platform where businesses can participate by sharing their own data, which is then anonymized and aggregated by the Federal government to be shared back with participating entities. This facilitates transparency across supply chain networks, especially at key nodes where temporal supply and demand mismatches could otherwise lead to delays and disruptions.

Additional initiatives to improve data availability and flow include the Department of Commerce’s newly established Supply Chain Center, which seeks to identify potential supply chain vulnerabilities and work with private sector partners to prevent supply chain disruptions ahead of time, and the Department of Homeland Security’s new Supply Chain Resiliency Center.

Increasing the transparency of supply chain data among market participants can improve market functioning, including by sending demand signals ahead of supply chain disruptions. Public sector intervention can also help resolve market failures through improved data flow, for instance when upstream firms will not invest in supply until they see sufficient demand, but downstream firms will not invest in products that rely on such inputs until there is sufficient supply.

Conclusion

The pandemic revealed significant vulnerabilities in our nation’s supply chains. The Biden-Harris administration initiated an ambitious work stream across government to improve and lastingly repair these linkages. Together with industry action, these efforts have helped to unsnarl global and domestic supply chains, leading to a broad re-normalization in the flow of goods, along with significant disinflation and even deflation. To build on these gains and implement lessons learned from the pandemic, we must put in place an ongoing, public-private policy infrastructure to monitor and improve supply chains. Central to this effort is working with international allies to further diversify supply chains, strengthening domestic capacity, and putting into place a data-gathering and analysis structure to monitor supply-chain health and resilience.

[1] Baldwin, Freeman, and Theodorakopoulos (2023) find that supply chains are much more exposed to foreign suppliers—particularly Chinese suppliers—than traditional measures would suggest. For instance, in 2018, China’s manufacturing sector produced about 40 percent of intermediate manufactured goods, accounting for more of global intermediate manufacturing output than all other advanced economies combined. This exposure is particularly pronounced in certain industries like vehicles, machinery and equipment, and electrical equipment—each of which have seen look through exposure rising by more around 5 percentage points between 1995–2018.